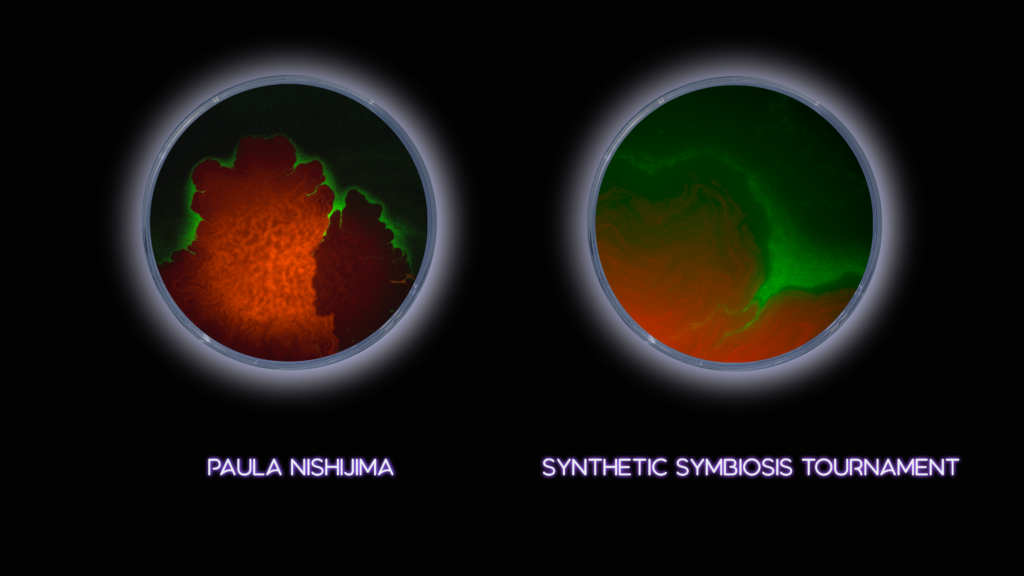

Documentación residencia artística ai2 de Paula Nishijima

Hi! I’m Paula Nishijima. I’m a Brazilian visual artist of Japanese descent, who lives in the Netherlands at the moment. My artistic practice is research-based, and I am developing the art project Synthetic Symbiosis Tournaments in collaboration with the Laboratory of Synthetic Biology and Biosystems Control from the Valencia Polytechnic University.

Before starting the residency at UPV, I posed the following questions to the scientists of the research group of ai2:

What is the role of cooperation in synthetic systems? Can a synthetic system be defined as selfish or altruistic? Is it possible to imprint a ‘cooperative marker’ into the genetic coding of an organism?

This set of questions has opened up other subset of questions, and a never-ending inquiry on not only cooperative behaviour in living systems, but also about the way how scientific thinking interpret the behaviour of living organisms.

Before we delve into the more philosophical questions, the first chapter of my residency in the UPV started with lab training. I had basic lessons about hands-on work in the lab, security and safety protocols, and theoretical content about the main collaborator in this art project: E. Coli.

Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria normally live in the intestines of warm-blood animals, such as humans. I found interesting the two-bladed sort of relationship we and other species have with these bacteria, as we benefit from some strains that live in our guts—they prevent other pathogenic bacteria from colonising our intestines. Some other strains, however, might be harmful. They can cause food poisoning through the ingestion of uncooked vegetables and raw meat, for instance.

In any case, in a project that is about cooperation and symbiotic relationships, it is certainly engaging to work with an organism that has always lived inside my body. Adding to this, the mind-blowing part was when I learned about the ‘synthesising life’ part of the research scientists do in the lab. And here starts my ludic journey into fluorescent colours and mixing DNA of different species. But before it, let me introduce my human collaborators in this journey: Jésus Andrés Picó Marco, Alejandro Vignoni, Yadira Boada and Andres Boleda. There’s also Carla Abadia, another artist-in-residence during this year at ai2, with whom I attended the lab training.

Jésus welcomed me in the department and gave me an overview about the research projects and people involved. We’ve gotten into the metaphors used in Science and their anthropomorphisation, a topic that I will develop further in the next chapters of this blog. Alejandro, who also has background in engineering was the one who gave us a master lecture about genetics, while Yadira and Andres explained the sequence of processes they perform for testing the bacteria and models they create in the lab.

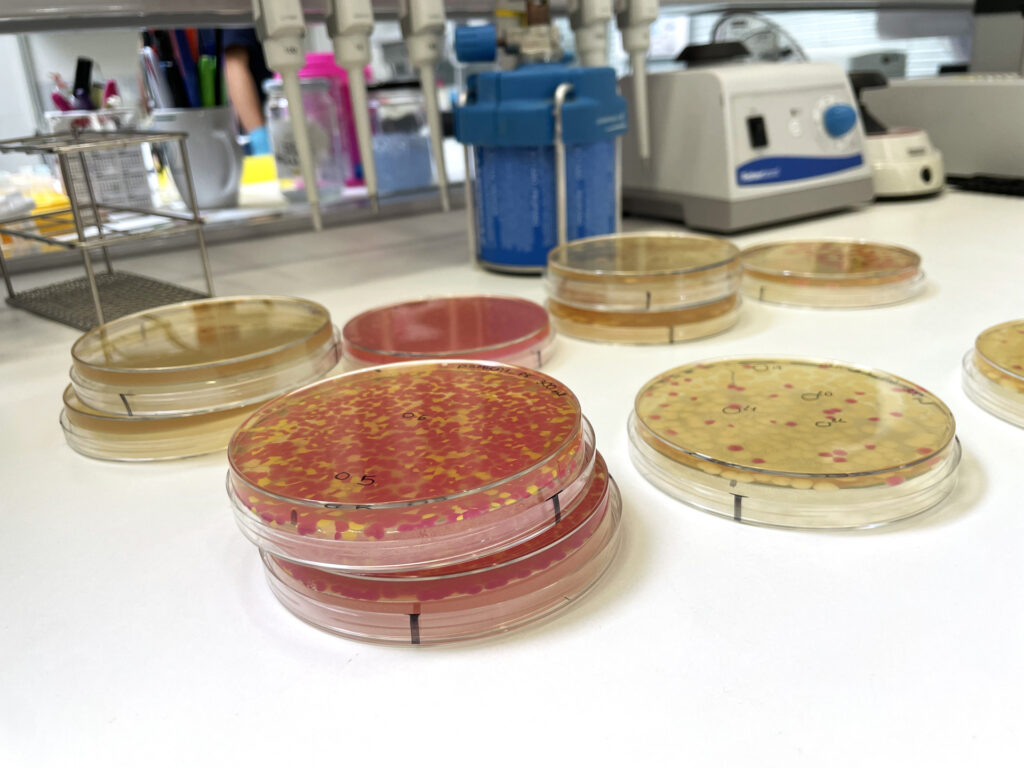

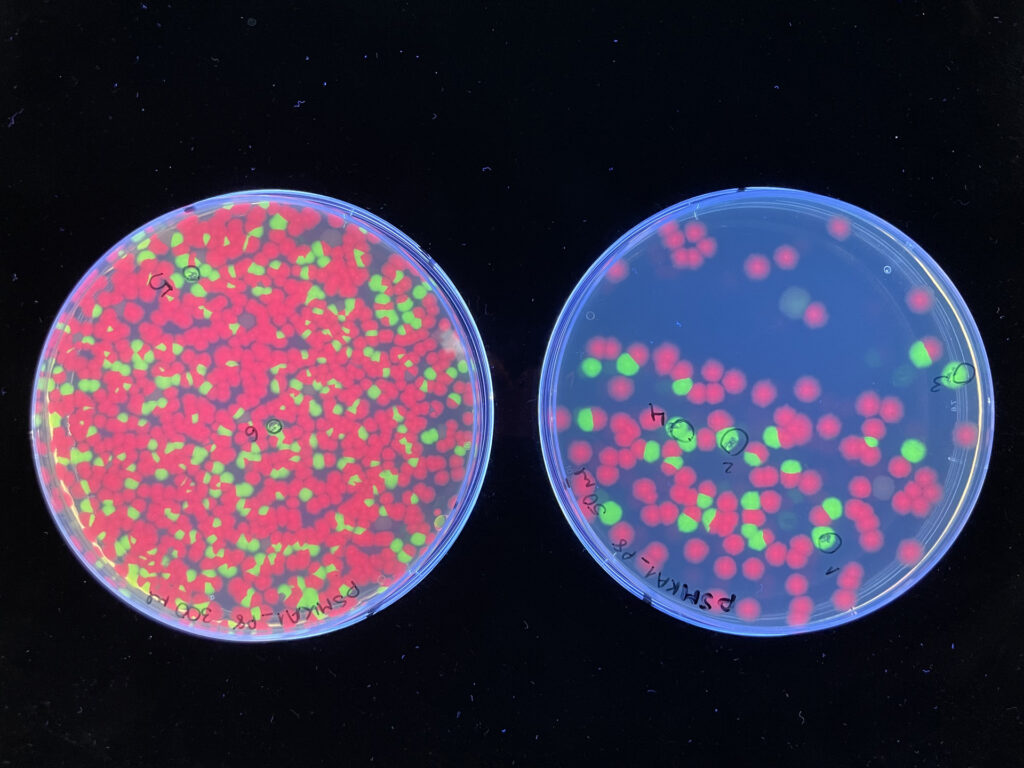

Coming back to fluorescent colours, the first thing the scientists showed me in the lab was two bacteria cultures in petri dishes. Looking at them with naked eye doesn’t say much about their glowing aesthetics, but once you put them under the right light—UV light—their hidden spectrum becomes visible to our human eyes. The result is a playful way to see bacteria growing as fluorescent green and red stains, which helps them to see and identify the bacteria when they are mixed in with other organisms.

E. Coli originally does not have this appearance though. The bacteria have been modified to produce a protein that confers them the luminous effect. The green fluorescent protein (GFP) comes from jellyfish, while the red ones (RFP) come from corals. In summary, the DNA from these different species of the deep sea was injected into the bacterium, so that it produces the same fluorescent protein. The GFP is the same that you have probably seen in Alba’s case, the green, fluorescent rabbit created by artist Eduardo Kac, who claims to have coined the word ‘bioart’. More than 20 years ago, the polemic bioart work has already put forth the ethical discussions around synthesising life. So, what does it mean exactly to ‘synthesise life’?